Juyondai was featured in dancyu magazine

July 25, 2025

Series: “The New Sake World Opened by Juyondai — The Work and Influence of 15th-Generation Brewer Tatsugorō Takagi.”

Hiroki burst onto the scene in 1999 with a vivid debut—a fresh, unfiltered, unpasteurized sake. Its later special junmai bottling has enjoyed unwavering popularity for years as a sake you can trust every time. Kenji Hiroki, ninth-generation owner-brewer of Hiroki Shuzō, is hailed—along with Juyondai’s 15th-generation master, Akinori Takagi (who took the name Tatsugoro in 2023)—as a pioneer of the brewer-owner movement and is admired by many young kura heads. This legend calls Juyondai “a truly special sake.” How did Juyondai shape him? We will tell Hiroki-san’s brewing story in two parts.

He came home at twenty-five; a few years later his father suddenly passed away. What, then, brought him into the spotlight?

In 2011 I interviewed brewers about “the most moving sake you’ve ever tasted.” Kenji Hiroki’s eyes lit up: “Juyondai Honmaru! One glass thirteen years ago showed me my future.” It was surprising to hear such praise—from a highly respected brewer and manager—for a honjōzō made by a younger peer and tasted more than a decade earlier. What had Hiroki-san been thinking about brewing before that life-changing sip?

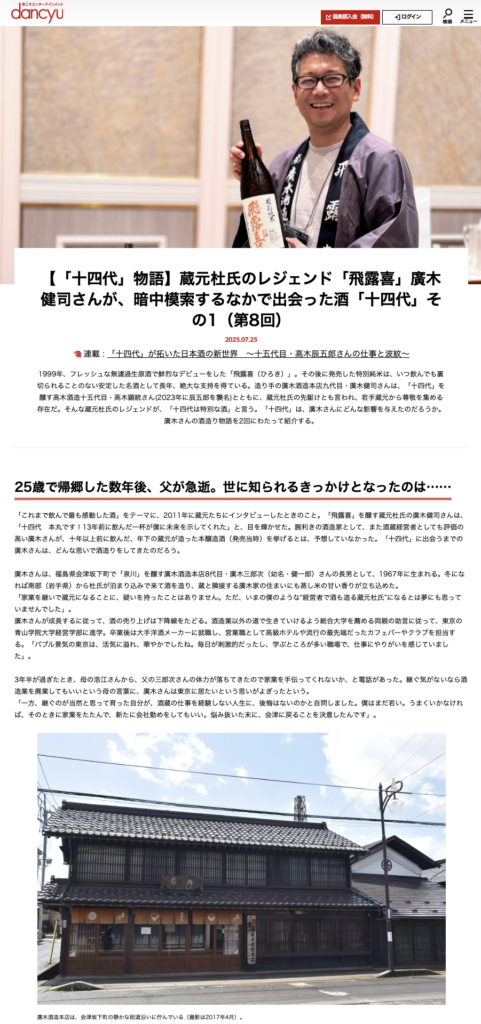

Kenji Hiroki was born in 1967 in Aizubange, Fukushima, the eldest son of Saburōji Hiroki—eighth-generation head of Hiroki Shuzō, brewer of “Izumigawa.” Every winter a master toji from Nanbu (Iwate) lodged at the kura to make sake, filling both the brewery and the attached family home with the sweet scent of steamed rice.

“I never doubted I would take over the family business. But I never imagined I’d become what I am now—a brewer-owner who runs the company and makes the sake himself.”

As he grew up, sake sales kept falling. His parents, wanting him to have options outside brewing, urged him to attend a full-fledged university, so he majored in business at Aoyama Gakuin in Tokyo. After graduation he joined a major Western-liquor company, selling to luxury hotels, trendsetting cafés, and clubs. “Tokyo during the bubble was vibrant and glamorous,” he recalls. “Every day was exciting, and the job taught me a lot; I felt real purpose in my work.”

After three and a half years, his mother Hiroe called: his father’s health was failing—could he help at the kura? She added that if he truly had no intention of succeeding, they could shut the brewery down. For a moment he considered staying in Tokyo.

“But I asked myself: would I regret never trying the work I was raised to inherit? I was still young; if things failed I could close the kura then and find another job. After much soul-searching I chose to return to Aizu.”

In the fall of 1992, at twenty-five, he joined the family firm and took over sales and deliveries. He loaded dozens of heavy wooden cases—ten 1.8-liter bottles each—onto a truck, leaving dark Aizu at 4 a.m., dropping off sake in other prefectures, then driving back the same night. Talk with customers was only about price cuts; flavor was never discussed. Retail price per bottle was under ¥1,000, yet sales kept falling; after fuel costs, profit was near zero. “I felt empty every day,” he says.

In 1996 the toji announced retirement due to age. Hiring a new master at a high salary was impossible, so father and son began brewing on their own.

“To my surprise, you can make ordinary sake fairly easily; you don’t need special skills. But I wanted to craft fine sake—work that mattered. I kept suggesting we aim for gold at the National New Sake Appraisal, but my father’s way was to cut costs, lower prices, and eke out a little profit, so he shot me down. We even grappled physically; our relationship worsened.”

Their first brewing season, begun in winter ’96, ended in early spring ’97. That May, Saburōji suddenly died at fifty-nine. Kenji felt both, “I can go back to a salaryman life!” and a rising desire to prove himself to his father.

“Father had protected the business his own way. If I brewed a sake I could accept, and then closed the kura, he would understand. So I became the ninth head and decided to make one last attempt worthy of our family.”

The turning point came in February 1998, during his second brewing season. NHK aired a nationwide program, “Exploring New Japan: Winter Brewing in Aizubange,” showing him at work. “I was chosen, I think, because my situation looked the bleakest among Fukushima breweries—good TV to inspire workers. I hated the idea of my misery going national, but I realized the footage would let my two-year-old son someday see me brewing, even if I later closed down. So I agreed to the interview.”

The day after the broadcast, a man named Kihachi Koyama called from Koyama Shōten in Tama, Tokyo. Panting with excitement, he said he ran a shop specializing in sake and would back Hiroki if he truly wanted to make great sake.

Hiroki was shocked such specialty stores existed. In the liquor firm he’d only dealt with big wholesalers; back in Aizu his clients were distributors and tiny local shops. Thinking he might compete on quality, not price, he sent a new junmai. But Koyama replied warmly yet firmly: “Show more of yourself in the sake. You’re still young. If you plan to brew with patience, I’ll watch and wait.”

Koyama had fallen for the bold taste of the first Juyondai brewed by Akinori Takagi at age 25 and had carried it since year one (see Episode 7). Watching a young heir turn “the flavor he believed in” into a star brand, Koyama now hoped for Hiroki’s own self-expression.

Yet “a sake that expressed himself” was a tough puzzle for Hiroki.

“I’d lectured my father about making fine sake, yet I had sampled very little else and had no clear vision. The junmai I sent Koyama just copied the then-popular ‘light, dry Niigata style’ and was thin and sharp.”

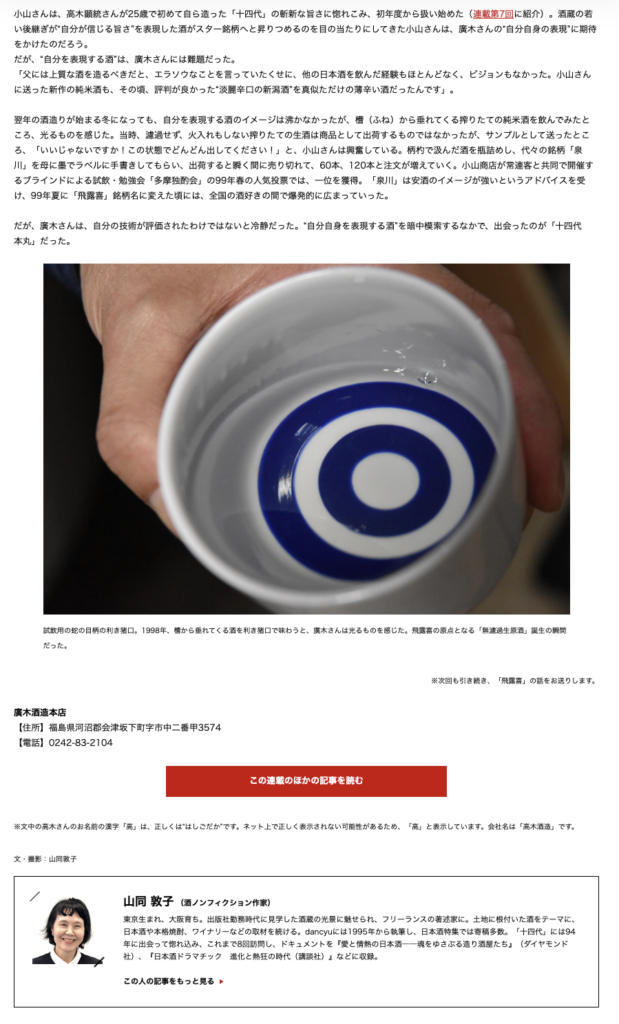

The next winter he still lacked a clear image, but when he sipped freshly pressed junmai straight from the fune, something sparkled. At the time unfiltered, unpasteurized namazake wasn’t normally sold, yet he sent a sample. Koyama burst out, “This is great! Ship it exactly like this!” Hiroki ladled the sake into bottles, had his mother brush the old brand name “Izumigawa” on labels, and shipped it; it sold out instantly, with orders jumping to 60, then 120 bottles. At Koyama’s blind-tasting “Tama Dokushakukai” in spring ’99, it took first place. Told that “Izumigawa” sounded like cheap sake, he renamed it “Hiroki” that summer—and the brand exploded among sake fans nationwide.

Still, Hiroki calmly felt it wasn’t his skill that was being praised. While groping in the dark for “a sake that showed himself,” he encountered Juyondai Honmaru.

![The Juyondai Story] How Takahiro Nagayama, Owner of Yamaguchi’s “Taka” Brewery, Was Shocked by Juyondai at Age 21 and His Life Was Changed (Part 10)](https://bacchusglobal.co.th/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/m9885-300x160.jpg)